What I learned about Japanese American Incarceration and today’s struggles for justice

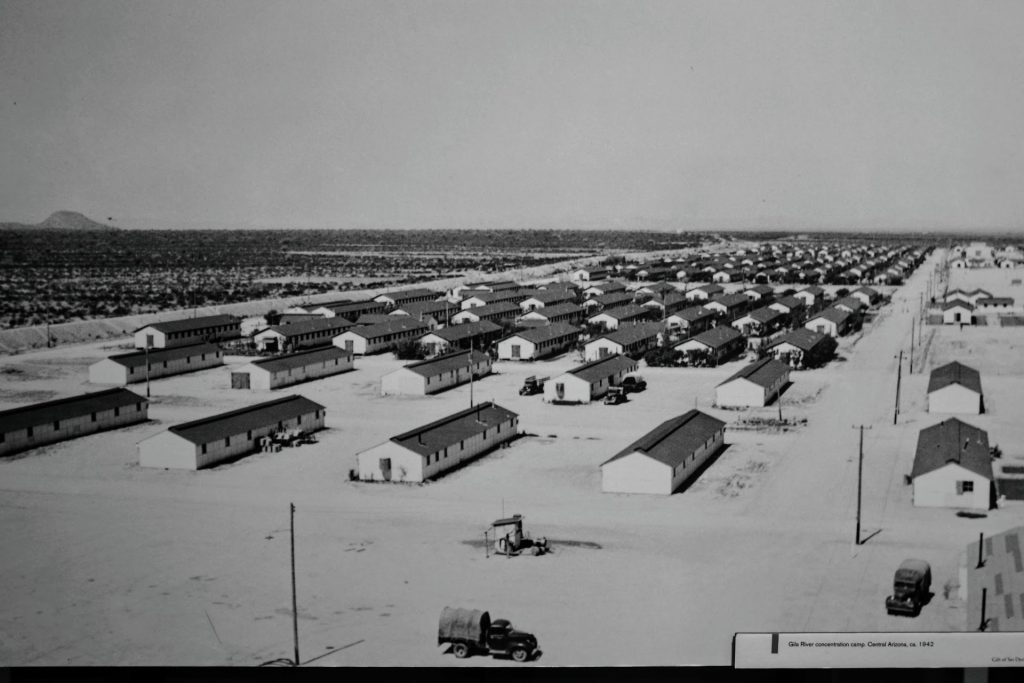

I had the privilege of attending the National Endowment for the Humanities seminar “Little Tokyo: How History Shapes a Community Across Generations” at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles this summer. This week-long institute delved deeply into the Japanese American experience through the lens of the Little Tokyo neighborhood in Los Angeles. Each day was filled with expert speakers, neighborhood tours, museum visits, and meeting with former incarcerees of America’s concentration camps, where 110,000 Japanese Americans and immigrants were incarcerated during World War II. There’s too much to share here, but I will share a few highlights and reflections as I continue to process this experience.

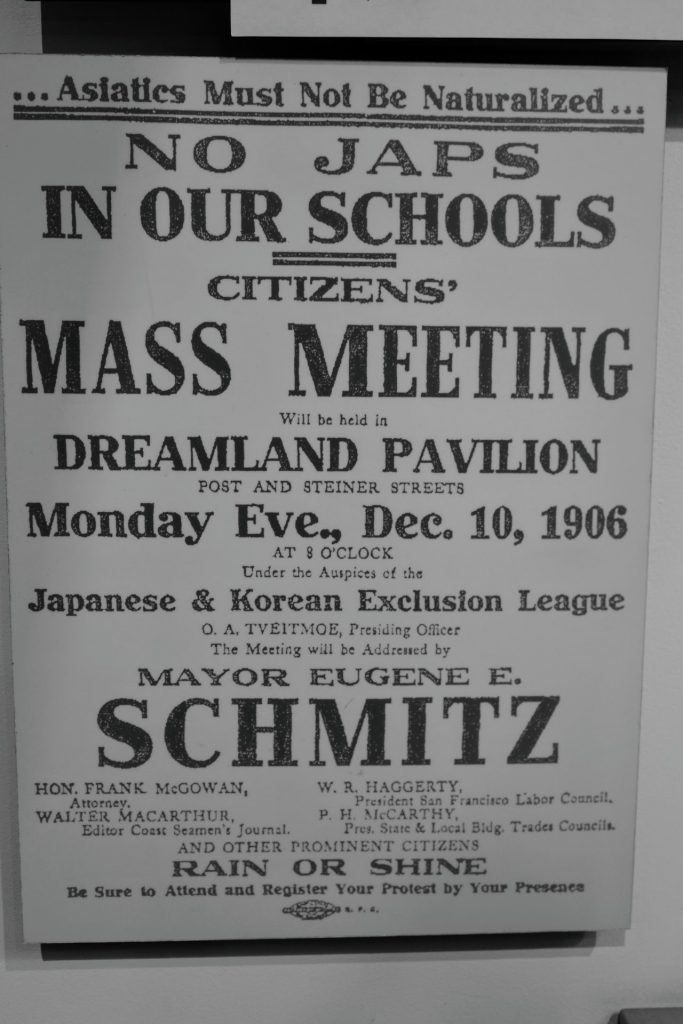

“Aliens ineligible for citizenship”

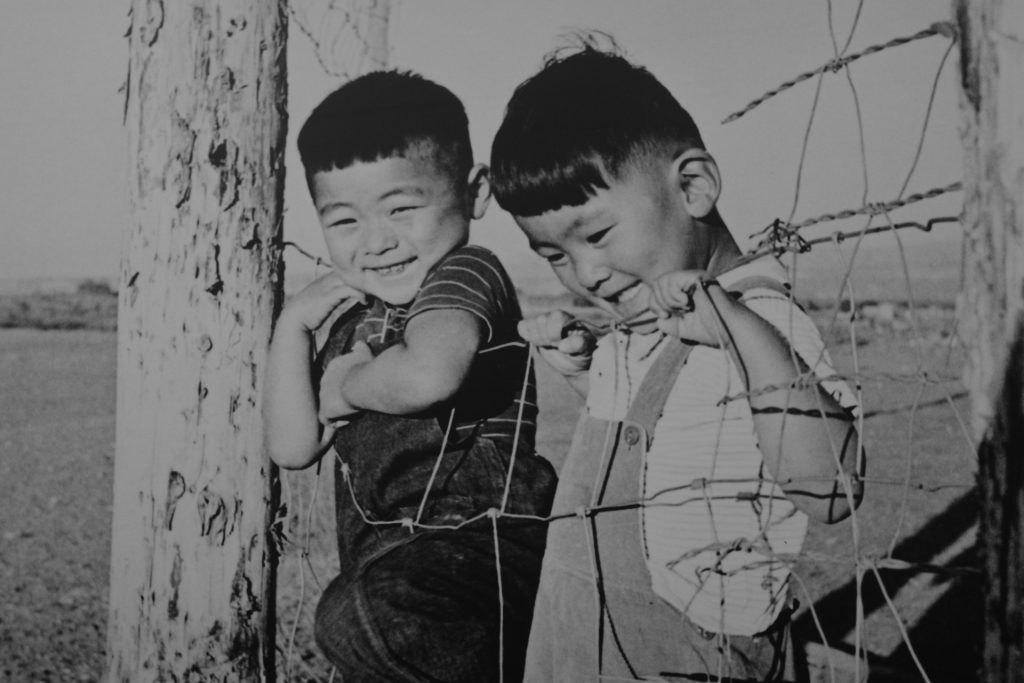

In 1942, the government used these four words to describe Japanese immigrants to the U.S. Though many had lived practically their entire lives here, they would not become eligible for citizenship until 1955. Their children and grandchildren, American citizens, were referred to as “non-aliens.” The government used many euphemisms to soften the harsh reality of incarcerating American citizens in concentration camps based solely on their race. Racetracks that temporarily housed the Japanese in horse stalls for months were called “relocation centers.” The entire operation was referred to as an “evacuation,” implying that its purpose was to somehow rescue the Japanese who lived in the U.S. Imagine if the government gave you less than a week to pack what you could carry, store or sell the rest, and leave behind your job and home only to move you and your family to a horse stall.

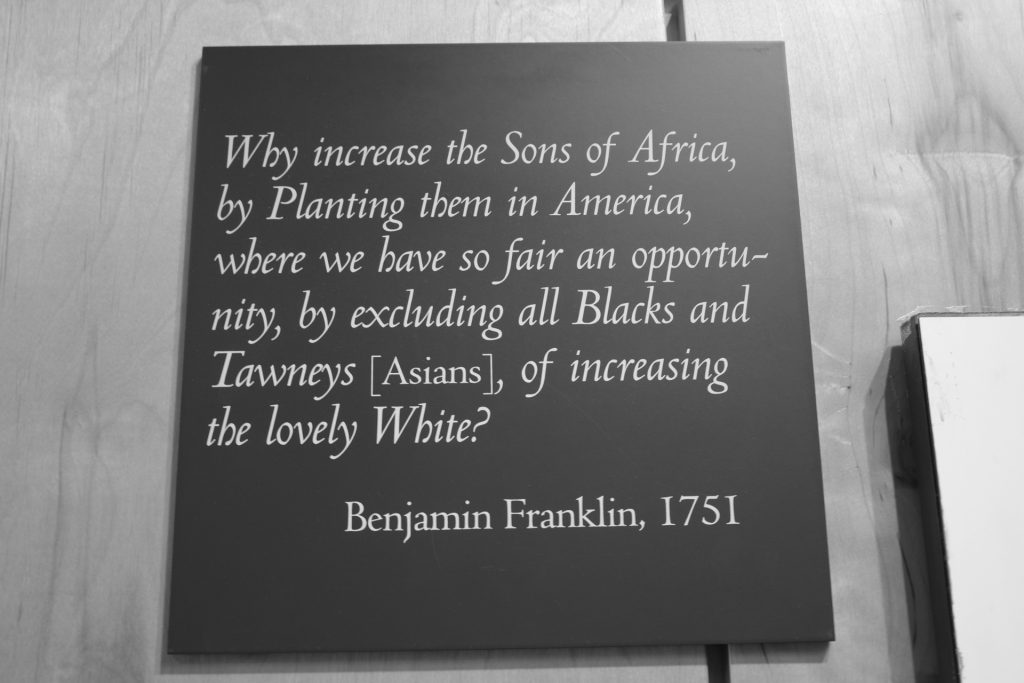

There are too many examples of euphemisms to list here. As I learned more, I couldn’t help but think how language is manipulated today. Those crossing our southern border in search of safety and a better life are called “criminals”, “drug lords”, and “rapists” who are part of an “invasion.” Language shapes our views of the world and the people we encounter. Learning this history has heightened my awareness of the danger of falling into the trap of stereotyping those who are in some way considered to be “different” from the dominant group (not white, straight, cisgender, male, Christian, able-bodied, middle class, etc.)

Bronzeville

When 7500 Japanese American citizens and immigrants were forcibly removed from their homes in Little Tokyo in 1942, their white landlords said it was unfair to them since they suddenly had no tenants to collect rent from! Where one set of racist policies posed a problem for a few white people, a solution came, also borne of racism.

Out of necessity, war production plants around Los Angeles ended their race-based discrimination practices which had denied African Americans employment. Blacks who came to California seeking these new jobs faced the same redlining that existed elsewhere in the country. Nine-five percent of the city was off-limits, so Little Tokyo, recently vacated, became “Bronzeville.” As many as 80,000 African Americans moved into a space where just 7,500 Japanese had lived.

Despite the crowded conditions and persistent racism (Blacks were largely limited in owning property, for example), Bronzeville became a thriving community with a lively music scene. In 1946, Charlie Parker played here with a young Miles Davis, making jazz history.

When the Japanese returned from incarceration, Blacks and Japanese lived side by side in a multicultural community. Racism however, won out in the end. Blacks began losing their jobs as white soldiers returned to work in the plants, and landlords opted to rent to Japanese Americans rather than African Americans. The final nail in the coffin that killed Bronzeville came in 1950 when the city of Los Angeles demolished an entire block of Bronzeville in order to build a new police station.

I am reminded of Elizabeth Wilkerson’s Caste, in which she points out that America’s problem with race has everything to do with not being on the lowest rung of the ladder. In this case, Japanese Americans, who dropped to the bottom of the racial hierarchy with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, were now one step above Blacks. Although “Little Bronzeville Tokyo” was a vibrant, productive, and harmonious community, racist practices that favored Japanese over Blacks put an end to it.

So Many Lessons

The story of Japanese American history is so much more than the story of incarceration during WWII. I learned of the contributions Japanese made to agriculture and railroads for decades before the war, and how those contributions did not earn them the right to citizenship. Once the work was done, many expected the Japanese to “go back to where you came from.” I learned of the anti-Asian hate that persisted across generations, including lynchings of Asian Americans. Even today, Asian Americans are viewed as foreign by many (“Where are you from?” “Your English is really good.”)

Japanese American National Museum

I was moved by the stories of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the segregated Japanese American unit that fought during WWII. The unit’s motto was “Go for broke,” and they more than lived up to it. It remains the most decorated battalion in all of US history, with the highest casualty rate due to the fact that they were given the most dangerous missions.

I learned of terrible choice young men had to make. Many chose to leave their family in a U.S. concentration camp in order to fight to free those in the Nazi concentration camps – all in an effort to prove their worthiness as U.S. citizens. Others decided to refuse to fight for a country that kept them and their family prisoner. Even soldiers on leave from the 442nd had to return to living behind barbed wire to visit their families. There were dire consequences no matter which path was taken. The choice tore families apart.

Japanese American National Museum

I learned that after suffering in detention for so many years, and losing nearly all possessions, that despite being given just $25 and a one-way bus ticket, former incarcerees did not want to talk about their experience. All they wanted to do was prove their loyalty to America and blend in with society.

Japanese American National Museum

On another day of the workshop, I was fascinated by the story of the long and seemingly impossible struggle for an official apology and reparations from the government. It is a story with many surprises, including how conservative President Ronald Reagan was convinced to sign a bill that many in his party opposed.

It was a long and arduous fight. When, at the final stages, an amendment was introduced calling for the reparations to be based on how many days survivors spent in the camps, rather than on a previously agreed-upon $20,000 for each person, Representative Ron Dellums made an impassioned argument against the proposed amendment. This is just one scene of a decades-long dramatic journey for justice.

There are so many other lessons. The great lengths to which the government hid the fact that their own reports indicated there was no threat from Japanese Americans or immigrants during the war. The Japanese Peruvians who were sent to America’s concentration camps, and eventually denied citizenship in either country. The Japanese American orphans who were removed from their orphanages to be placed behind barbed wire in the camps due to the threat they posed to our country’s national security. The handful of white spouses who chose to enter the camps to remain with their biracial children. The amazing resourcefulness of the incarcerees under extremely harsh conditions. The absurdity of the loyalty questionnaire and the terrible repercussions it led to no matter how one answered. The four Japanese Americans who brought their cases to the Supreme Court in their fight for justice. The enduring racism that persisted when incarcerees were finally allowed to leave the camps. The persistent community activism that continues today so that Little Tokyo doesn’t become just a “plaque on a wall” or a gentrified tourist trap as has happened to other immigrant neighborhoods. And so many more lessons.

Allyship

One of the most powerful lessons I learned was that of allyship. Japanese Americans have persistently stood in solidarity with other marginalized groups. Combating Islamophobia, supporting Black Lives Matter, and ending all forms of unjust incarceration have been major causes for the Japanese American community.

Organizations like Tsuru for Solidarity fight to end unlawful detention, including that of child migrants and others along the US border with Mexico. Some of the government’s Emergency Intake Sites (described as “warehouse-like prisons for unaccompanied children“) are even located where Japanese incarceration camps once stood during WWII.

Having suffered through incarceration while few spoke out against it, Japanese Americans understand the importance of speaking out against injustice everywhere. They know that the racist policies against Japanese that went unchecked for decades made it possible for the concentration camps to be built overnight and go largely unchallenged by many Americans.

Japanese American National Museum

Perhaps the biggest thing that sticks with me is that we are living in a similar time of fear – fear of outsiders, of invasions across the border, of disease carried by people who look different from us, of people who refuse to hide their “differences,” fear of teaching truth to our children, fear of so many things.

Throughout the week, I was constantly reminded of the importance of not only avoiding the temptation to give in to the fearmongers, but of taking action to prevent and stop injustice. One way I try to do this is by working with the Westerly Anti-Racism Coalition. Anyone who wants to know more about this organization (or subscribe to our newsletter), visit the Westerly ARC website!

In the spirit of the 442nd, we must “Go for broke” in the fight for justice.

Teachers: Click below to use or modify the lesson plan I created on the Smithsonian Learning Lab as a result of attending the institute.

A few more images from my first trip to Los Angeles

Thank you to the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Japanese American National Museum for making this seminar possible. I relied on my many pages of notes and various resources for the content of this post. Please notify me if you see any errors. I especially want to thank the presenters at our daily workshops, including the staff at the Japanese American National Museum, the many visiting scholars, and the survivors of America’s concentration camps who inspired us with their stories every day.

| Lynn Yamasaki, Director of Education | Japanese American National Museum |

| Sohayla Pagano, Education Specialist | Japanese American National Museum |

| Nina Nakao, Virtual Learning Coordinator | Japanese American National Museum |

| Jenna McGuire, Education Assistant | Japanese American National Museum |

| Brian Fong, Program Director | Facing History and Ourselves |

| Emily Anderson, PhD, Curator | Japanese American National Museum |

| Hillary Jenks, PhD, Director of GradSuccess | University of California, Riverside |

| Kristin Fukushima, Managing Director | Little Tokyo Community Council |

| Mitchell T. Maki, PhD, President and CEO | Go for Broke National Education Center |

| Dan Kwong | Performance artist, writer, teacher and visual artist |

| Junko Goda | Performance artist, actor |

| Kristen Hayashi, PhD, Director of Collections Management | Japanese American National Museum |

| Karen Ishizuka, PhD, Chief Curator | Japanese American National Museum |

| Kathy Masaoka, Co-Chair | Nikkei for Civil Rights |

| Mike Murase, Community Historian | Nikkei Progressives |

| June Aochi Berk, Community Historian | Former incarcaree |

| Bob Moriguchi, Community Historian | Former incarcaree |

| Hal Keimi, Community Historian | Former incarcaree |

| Richard Murakami, Community Historian | Former incarcaree |

| Mas Yamashita, Community Historian | Former incarcaree |

| William “Bill” Shishima, Community Historian | Former incarcaree |

August 17, 2022 @ 10:53

This is very informative and succinctly written. It sounds like a profound experience for you. Thank you for sharing this horrible part of our history.

August 21, 2022 @ 16:26

Thanks, Julie, and Congratulations to you and Dale!

August 17, 2022 @ 22:21

Tremendous reporting, Tim. I was aware of some, but not all of this horrific chapter in our history. Thanks so much for sharing it in such depth.

August 21, 2022 @ 16:27

Thanks, Stevi. I learned so much.

August 18, 2022 @ 18:57

Keep teaching, Tim, just in a different setting than the classroom. Our world peace needs to hear and respond to kind people like you! Education through understanding the lives of others.

August 21, 2022 @ 16:27

Thanks as always!

August 24, 2022 @ 19:01

Thank you for sharing, Tim……I always learn so much from you and enjoy traveling with you!

September 5, 2022 @ 17:40

Great to see you and Jimmy in Stop and Shop! Have a great first week of school!

September 3, 2022 @ 21:27

Great title and stories on anti racism in Japan . You’re my hero Tim!

September 5, 2022 @ 17:41

Thanks, Eric! You are a constant inspiration for me to keep writing, traveling and taking photos.

September 5, 2022 @ 09:42

The journey is understanding, then empathy, and finally sympathy.

Just don’t forget this journey is still your own and does not mean we know, just that we try to know.

I can only imagine being an American of Japanese decent or birth at this time. But I do know that it would likely be wrong.

Well written

September 5, 2022 @ 17:44

Thanks for checking out my blog and for the comment, David. I fully agree.